What implicit bias looks like

And how to reduce its impact in the classroom

This is a story about implicit bias in the classroom. In Part 2, I’ll share a story about seeing my own implicit bias in the classroom, and in Part 3 I’ll discuss ways to avoid implicit bias acting out in the classroom. But first, an unusual story about texting with friends because, strangely, it helps illustrate the point.

Part 1: Texting with Laura

Last Thursday morning, I was texting with my friend Laura Paul who was traveling for a conference. She asked me how I was feeling (I had a bad cough) and I asked her how the conference was going. She replied about her dinner with colleagues and then the three bouncing dots indicated she was writing more, so I switched to another app to wait for her reply.

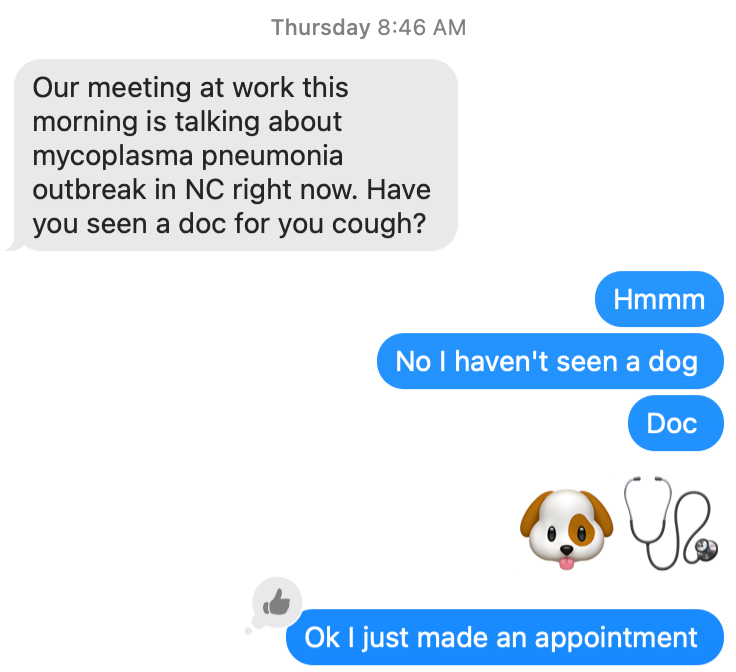

When Laura’s text came in, she encouraged me to see a doctor because there was a pneumonia outbreak in our area. This was slightly odd; Laura Paul’s expertise is in agricultural economics, not epidemiology, but I didn’t think much about it. I quickly fired back a series of texts (missing an autocorrect of doc to dog, then riffing on that mistake).

After going to the doctor (I did, in fact, have pneumonia), I went back to the text thread to thank Laura for her suggestion, but the whole conversation was missing. There was just her text about her meal with colleagues. I was mystified – what had happened to our entire conversation?

Then it dawned on me: While texting with Laura Paul, my other friend, Laura Paye (who is a primary care physician) texted me about the pneumonia outbreak. Because I was expecting a text from Laura Paul, I didn’t pay much attention to the name when Laura Paye texted me!

My mistake sunk into me with horror, and I immediately went back to my text thread with Laura Paye to see if I had said anything inappropriate. Laura Paul and I can have some pretty silly, sometimes tongue-in-cheek interactions over text (hence the dog + stethoscope emojis), and I was worried I had fired off some joke that would have been weird with Laura Paye. But it was fine. Laura Paye never needed to know that I thought she was Laura Paul when I texted with her!1

But that feeling – the “oh no, did I act inappropriately when I thought the situation was X but it was really Y?” – I have had that feeling in the classroom before, and I want to share it because I think it reveals implicit bias where it is usually well hidden.

Part 2: The case of two Taylors

I met Taylor in my Spring 2021 General Biology I course (48 students). Because of the pandemic, the course was all online, with weekly synchronous online meetings. For privacy reasons, I never asked my students to turn on their cameras. Taylor engaged in our synchronous course meetings through the chat and kept in regular contact with me via email, but I never saw her. She was an engaged student, though she ended up failing the course.

The next semester, Fall 2021, Taylor enrolled in my General Biology I course again – this time (for the first time since the pandemic began) in-person!

I remember meeting a Taylor on the first day of class, but that Taylor was a man, not a woman. I remember thinking, “Oh I must have two Taylors this semester!” The roster can change at the last minute, and I wasn’t sure if my printed roster was up to date when class started. This was a class with multiple duplicate names – a John and a Jon, two sisters with the same last name – so I wasn’t phased by the prospect of two Taylors: the man I had just met, and the woman from my online course last spring who appeared to be absent on the first day of class.

But when class finished that day, I went back to check the roster online and there was only one Taylor – the same name from my spring online course. That’s when it hit me: there were not two Taylors, just the one – a man. For some reason, all of spring semester I had assumed Taylor was a woman, but he was actually a man.

Then, just like my realization when texting with Laura Paye, I had that horrified feeling: During the entirety of the spring semester – in all of our emails and all of our interactions in the chat during the synchronous online meetings – did I treat Taylor inappropriately given that he was actually a man and not a woman like I had assumed?

As a woman who navigated a PhD with a male PI and an all-male PhD committee, and who was often the only woman to ask a question at science seminars during my postdoc at MIT, I am acutely aware of gender bias in STEM. I work hard to convey to my students that anyone can be a scientist2, and I work hard to see the potential in all of my students, regardless of their gender, race, socioeconomic background, sexual orientation, or any other identity.

But also, I remembered this: At one point during the spring semester, as I lingered after an online class meeting that had been about cellular respiration and how organisms gain and lose mass, Taylor wrote in the chat about struggling to gain weight and feeling really thin. I remember having the flash thought, “Oh poor girl, you’re model-thin, how awful” before I checked myself. I’m pretty sure I responded with something about how different bodies are different – some are thin, some are not, and that’s ok. But – full transparency here – I had that initial, judgy thought, thinking that it was a little rich for a very skinny woman to be complaining about being skinny in a society that exalts skinniness in women.

Of course, skinniness in men is not exalted in our society. Ursula, the sea witch from Disney’s 1989 movie The Little Mermaid, illustrates this sexist bias in her song “Poor Unfortunate Souls:”

This one longing to be thinner

That one wants to get the girl

And do I help them?

Yes, indeed

In our society, thinness is exalted in women, but not in men, and that bias is ingrained in me, even though I actively don’t believe it on a cognitive level.

Would I have responded differently to Taylor’s complaint about being too thin if I had known he was man? I’m not sure. But I do know I would have thought differently. And that, dear reader, is what implicit bias looks like.

Part 3: How to reduce the impact of implicit bias in the classroom

You might see my story about Taylor and say, “Well, nice job, you checked yourself and didn’t let your knee-jerk thought come through in your actions.” Well, yes, but how many other times has my implicit bias affected my thinking, and in turn, affected my actions in ways that did affect my students directly?

The thing about implicit bias is that it is implicit, which means you usually aren’t aware that it’s even there. But we all have it. Being raised in a society means your mental frameworks have been shaped by that society’s values, expectations, and biases – the good, the bad, and the ugly. Implicit bias is a part of your thinking, whether you like it or not.

I teach at a community college, so I work with an especially diverse student population. I worry about how my implicit biases might “act out” in the classroom, unintentionally advantaging or disadvantaging certain students. I know that I can’t catch or correct every implicit bias that might rise up in my mind (again, it is implicit), so I work hard to build structures that help to bias-proof my courses, especially my grading policies. Here are some of the things I do, and why.

Problem 1: Case-by-Case Decisions

Making “case-by-case” decisions about extraordinary circumstances is a prime opportunity for implicit bias to act out. To avoid making case-by-case decisions, I use structured policies to deal with most of the situations that typically need case-by-case decisions.

Late Work

I created a structured late work policy using tokens so I don’t have to decide whether to accept late work. Every type of assignment has a late work policy that is stated in the syllabus that explicitly describes how I will handle late work for that type of assignment. This eliminates most of my case-by-case decision making. I describe my late work policy in more detail in this blog post and I talk about a variety of equitable late work approaches in this 25-minute presentation.

Absences

Before the semester starts, I plan for how I will handle it if a student needs to miss an exam or lab day. This way, when a student writes about an emergency that keeps them from class on an important day, I lean on policies I’ve already crafted rather than creating a (possibly-bias-influenced) exception for that one student. I never include attendance in the grade, because it harms students.

Problem 2: Judging Student Performance

Making a judgment call about a student’s performance is another opportunity for implicit bias to act out. I try to avoid making judgment calls about student performance, and when I do, I use anonymous submissions.

Participation

Looking at a classroom and making a call about who is, and isn’t, participating is a bias-prone activity. I’m more likely to notice the contributions of some students compared to others, and I’m more likely to think some behaviors constitute participation relative to others. I don’t grade for participation anymore, but when I did, I made sure to use objective measures of participation, like clicker responses, exit question submissions, or responding to forum posts online. Other options include having students self-assess by identifying the ways they have participated in class.

Grading Student Work

Extensive research has shown that when instructors know the identity (or presumed identity) of the student who submitted an assignment, they grade otherwise equal performance more harshly for certain identities. To avoid the impact of my implicit biases when I grade student work, I have students submit work anonymously. This works best for one-off assignments and becomes harder to implement when working with students on progressive assignments that build on previous feedback. Of course, some types of assessment – like oral exams – are impossible to do anonymously. But where it is feasible, anonymous submissions can substantially reduce the impact of implicit bias in grading.

This last point - making a judgment call about a student’s performance is an opportunity for implicit bias to act out – is why I am particularly suspicious of the equity impacts of ungrading and collaborative grading. I’ve written more about that here.

I am human, and I teach humans, and it is impossible to eliminate my implicit biases from the classroom. Sometimes I think the benefit of, say, doing oral exams, outweighs the potential negative impact from my implicit biases. But I still think it’s important to recognize the ways that implicit bias can act out in the classroom, and work to build course structures that reduce that impact as much as possible.

Not everything you read on the internet was written by a human. For full transparency, here is how I used AI to help me write this post:

I did not use AI in any way for this blog post.

I have, in fact, told both Lauras this story and had a good chuckle about it.

In particular, I assign Scientist Spotlight homework assignments and they can be very impactful, especially for students who don’t identify with mainstream images of scientists.