Redesigning Intro Bio Part 5: Grading

Note: This was originally written on August 15, 2022 and posted on my personal website.

Equitable Learning vs Equitable Grading

In Joe Feldman’s book, Grading for Equity, he makes the compelling case that a student’s final course grade should reflect only their learning, not their behavioral compliance. I agree: I don’t actually care whether a student does the homework, as long as they demonstrate proficiency in all of the learning objectives. In Feldman’s view, including non-assessment scores in the final course grade (such as completion of homework, or turning in assignments on time) perpetuates inequities, because doing so penalizes students who are more likely to experience instabilities at home or work that impact their ability to complete or turn in work on time.

In contrast to this viewpoint, Kelly Hogan and Viji Sathy argue in their book, Inclusive Teaching, that to improve equity and inclusion, courses should be highly structured. A highly-structured course includes (among other things) non-optional assignments, such as homework, that are designed to help students learn. The key to their argument is that the assignments must be non-optional — i.e. it must be included in the final course grade — to encourage all students (especially the ones who need it) to complete the assignment. On this I agree, especially for Introductory-level students, many of whom enroll in a course to fulfill a requirement; these students may not have much internal motivation to learn the material, so earning points for completing assignments may improve their learning.

Yikes. How do we reconcile these opposing — yet both compelling — arguments?1 It seems that at the heart of this apparent conflict is the distinction between equitable grading (Feldman) and equitable learning (Hogan & Sathy). Of course, I want both!

Multiple Grading Schemes

My (imperfect) solution is to use Multiple Grading Schemes.2 Essentially, I have multiple grading schemes that weight the components of the course differently; one scheme includes homework and formative assessments, and another scheme includes only summative assessments. That way, a student who struggles to perform well on high-stakes exams can get a “grade boost” by demonstrating consistent effort throughout the semester, whereas a student who demonstrates mastery on the assessments is not penalized for skipping the homework if they learned the material without it. At the end of the semester, I calculate each student’s grade using each grading scheme, and give them whichever is highest. This way, there are multiple ways a student can be successful in the class without requiring students to jump through specific behavioral hoops.

I think this system is more equitable than a single-grading scheme system. Last year, after I gave a talk about Multiple Grading Schemes at my institution, the Math Department adopted it for all of their classes. Preliminary course grade data from those classes suggest that up to twice as many Black and Latino students benefited from having Multiple Grading Schemes compared with White students. Again, these are preliminary data; there is more work to be done before I think this conclusion is fully supported by the data.

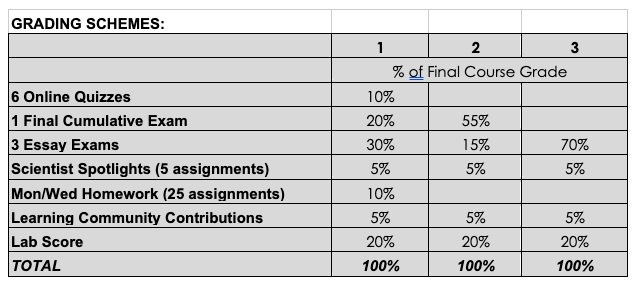

You can see the grading schemes for my newly-designed course here.

Grading Scheme 1 is the “typical” grading scheme that includes all the components of the course, including homework (which is graded on completion only). Assessments for this Scheme equal 60% of the final course grade and are evenly distributed between the higher-level Bloom’s “Essay Exam” assessments and the lower-level Bloom’s quizzes/final cumulative exam. Grading Scheme 1 benefits students with lower summative assessment scores and consistent performance on the homework and online quizzes.

Grading Scheme 2 weights the Final Cumulative (lower-level Bloom’s) most heavily, though I still include essay exams as 15% of the grade for this scheme, because I think that higher-level understanding is important. This scheme benefits students who develop a strong content-level understanding, but struggle to integrate the ideas for higher-level Bloom’s assessments.

Grading Scheme 3 is based almost entirely on the Essay Exams, which are higher-level Bloom’s assessments (and incorporate reflective revisions). I reason that students won’t be able to perform well on these assessments without strong content knowledge, so it’s not necessary to include content-level assessments (quizzes and final cumulative exam) in the final course grade. If a student blows it out of the park on the essay exams, I think an A would be warranted even with low quiz and homework scores.

Note that I include Scientist Spotlight assignments in all Grading Schemes. As I mention in Redesigning Intro Bio Part 1: Start at the End, Scientist Spotlight homework assignments are aligned with one of my primary learning objectives: Describe the characteristics of a scientist, and personally relate to one or more scientists. I think this is an important equity-related learning objective for all STEM fields, which have historically been dominated by white male representation. I want my non-white male students to know that they, too, can become scientists.

I also include “Learning Community Contributions” in all of the grading schemes. After reflecting on this thought-provoking tweet, I decided to add a primary learning objective for my course of Demonstrate evidence of personal contributions to the classroom learning community. An important goal in my course is for students to contribute to — and benefit from — a collaborative, supportive learning environment. At the start of the semester, students will create a list of behaviors that can earn points for this category, then at the end of the semester, students will complete a reflection in which they collect and discuss evidence of the ways they contributed to our course learning community. I’ve never done this before, but I’m hopeful it will create the structure to support all of my students in their learning journey.

Late Work Policies

An equitable classroom is one that allows students to turn in work late, because some students are more likely to experience instability at home or work that impacts their ability to meet regular course deadlines. (If a student has to choose between turning in their homework on time, or picking up an extra shift at work that will help them pay for groceries, I hope they pick up the extra shift!) But, an equitable classroom is also a structured one, where students are expected to regularly complete the assignments that are designed to help them learn, and to do it in time to benefit from that learning!

Yikes (again). How do we balance the apparent conflict between the (equity-based) need for deadline flexibility with the (equity-based) need to provide a highly-structured environment for students?

My solution is to use Late Work Tokens. Students start the semester with 3 Late Work Tokens, which they can use to turn in any assignment late with no grade penalty. In the syllabus I outline which assignments are eligible for Late Work Token redemption. For example, homework assignments and essay exam revisions are eligible, but online quizzes are not eligible after the answers have been released. (A missed quiz earns a 0, but two of the Grading Schemes don’t count quiz scores at all, so students who earn a 0 for a quiz still have access to a high grade.)

If students run out of tokens, they can earn more by meeting with me or our Department “Success Coach” to discuss time management strategies.

Because not all students feel comfortable emailing a professor to ask for any type of accommodation, I make it easy for students to redeem Late Work Tokens. I created a tab in my Learning Management System called “Deadline Extensions” which takes students to a Google Form where they can redeem a Late Work Token.

My goal is to balance learning equity with grading equity. I know my grading system isn’t perfect. For that matter, I know my redesigned learning objectives and course structure aren’t perfect. But as I use these grading systems and teach my redesigned course, I will pay attention. What works? What doesn’t? Who is falling through the cracks — and how do I help them? With these observations — and with good ideas from the literature and my communities of practice — I will refine, renew, and adjust my course. Perfection isn’t possible, but getting better is.

Thanks for reading my blog! This is my final post about Redesigning Intro Bio. Classes start tomorrow; it’s time for me to buckle down and live into the structure I’ve designed for this semester!

It’s worth noting that the equity impact of a high-structured course has been demonstrated in the literature, whereas the equity impact of including only summative assessments in the final course grade has not been published, to my knowledge.

Multiple Grading Schemes is not the only way to balance grading equity with learning equity, but I think for the Introductory classroom, using a points-based system can be more familiar and therefore more manageable for students in their first semester of college. I’ve used Collaborative Grading (a term I prefer over “ungrading” but which leans on the same principles) in General Biology II, where it generally worked well. But for the first semester course — especially one with many students taking the course to fulfill a requirement — I think it can be beneficial to stick with a traditional points-based system and deviate within that structure to improve equity in learning and grading.