In 2013, the first time I taught upper-level Biology classes, I noticed that my students paid almost no attention to the data figures in primary literature papers. I told them the figures were more important than the text. I pleaded with them: Look at the figures! I used clever assignments designed to make them focus on the figures of the paper, not just the text.

Still, when I asked them, What is the conclusion of this experiment?, students would search the paper’s text – not the figures - for an answer.

BUT THE WHOLE REASON I HAD THEM READ PRIMARY LITERATURE WAS TO LEARN TO THINK SCIENTIFICALLY! BY MAKING CONCLUSIONS BASED ON DATA! Why was it so hard to get them to do that?

It turns out, this isn’t just a me-problem. Learning how to read primary literature articles is hard! There is a whole literature on teaching strategies designed to help students learn how to read primary literature articles (see this excellent 2023 review by Lara Goudsouzian & Jeremy Hsu). This excerpt from Round & Campbell (2013, CBE-Life Sciences Education) perfectly captures my experience:

We have observed that introductory and upper-level students often approach a research article as they would a textbook, focusing on the narrative of the paper as fact, with the figures subordinate to the text. Undergraduates come to class having underlined and highlighted large portions of the text, yet they are often unable to describe the rationale for an experiment or interpret data presented in the figures.

Teaching students how to think scientifically – by making conclusions based on data, not just the words of others – is foundationally important to me. (It’s also a key component of Vision & Change, the guiding framework for teaching in the higher ed biology classroom). So what could I do?

A Delightful Surprise

Fast forward to yesterday. This happened:

Students were engaged in a Jigsaw activity (more on Jigsaws below) where they were explaining scientific case studies to each other. While it’s really cool to watch students explain science to each other, I was struck by this – every student who explained a case study pointed at the data figures in their jigsaw handout. And the students who were listening took notes on the data figures in their handout.

I wasn’t expecting this.

Don’t get me wrong, I was expecting to love the educational dynamic during the Jigsaw (there’s something so powerful about watching students explain science to each other!). But I was blown away by their collective emphasis on the data figures. I got them to focus on the evidence, not just the text! Hooray!

How did we get here?

Some relevant background information about my course: I’m teaching General Biology II at a community college in NC. My class has 20 students, which I have divided into assigned teams of 5 for the entire semester. This is my fourth semester teaching this course, and my second time using my own curriculum.

In the Fall of 2022, tired of using textbooks that didn’t fit my pedagogical values or my students’ educational needs, I designed my own textbook-free curriculum (here’s how it started; here’s my reflection after the first semester).

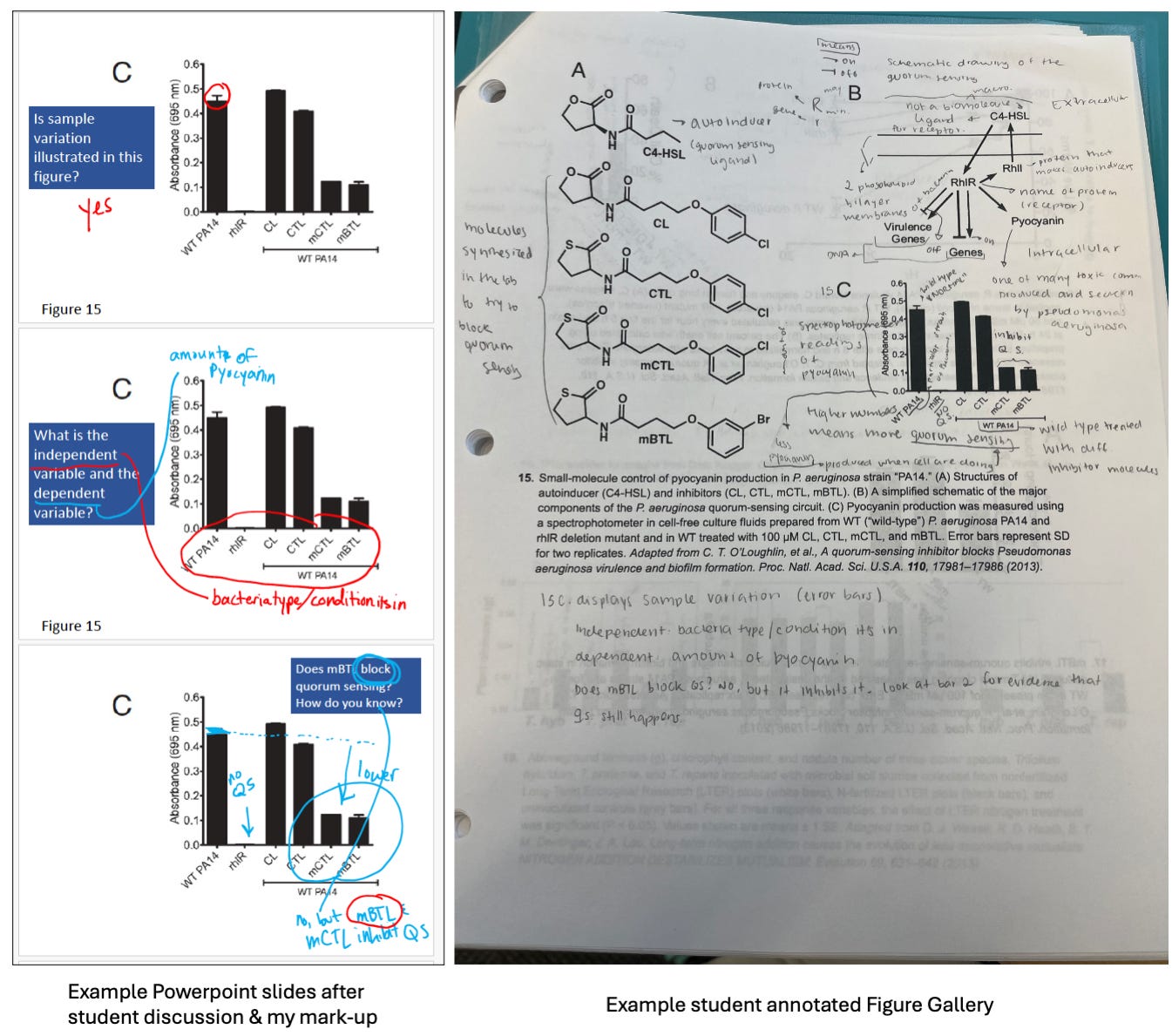

For Gen Bio II, the redesigned curriculum involves one-week case studies on different topics that span core biology concepts. For each case study, students read or watch videos about basic biology concepts before class (here is my “textbook” they use for this), then during “lecture” I present key figures from primary literature. I model how to annotate figures by using a tablet to take notes on powerpoint slides during class. They take notes on the figures in their paper copy of the Figure Gallery.

In my course, students don’t actually read primary literature articles. Instead, they are introduced to key figures that tell a scientific story1 during class. I explain the experimental design for each figure and use discussion-based prompts to scaffold the process of making conclusions from the data. About 80% of the exam questions reference the Figure Gallery, for example:

4. One of the ways that conservationists are working to preserve corals in the face of rising sea surface temperatures is to facilitate natural selection. Natural selection can cause a shift in the coral population to be more tolerant of the stresses that come with high sea surface temperatures.

a. What are the 3 components necessary for natural selection to occur?

b. Cite data from the Figure Gallery supporting the claim that one of the components you listed in (a) is true for coral species in warmer temperatures. Explain how the data support your claim.

After Exam 1, students learned quickly that the Figure Gallery matters, and that the most important thing they can do to prepare for the next Exam is annotate the figures we discuss in class.

So yeah, I focus on data figures in this course a lot. All semester long, I expect them to interpret data, graph data2, and see if conclusions are supported by data.

But what’s so cool is that my focus on data figures when I am teaching them transferred to when they are teaching each other. I was blown away by this! And I thought it was worth sharing.

Why I love a good Jigsaw

A classroom Jigsaw is an active learning activity designed to build student expertise in one topic and exposure to several other topics.

It works like this: Students are divided into teams. Each team becomes the expert on a unique topic. In my case, I provide students with a Jigsaw document (here is an example) that includes four case studies that are about 10 pages each. Each case study is centered on one or two primary literature articles and includes introductory text from secondary literature sources and a brief description of the handful of key figures from the primary literature paper(s). Students read their assigned case study as homework before class. During class, teams spend about 20 minutes making sure everyone on their team understands their case study, including going over the data figures and answering guiding questions.

Then, I mix up the teams so there is one student “expert” for each case study on each team, and they take turns so every student explains their case study to the rest of the group.

I love the classroom Jigsaw because:

since each student is the only expert on their topic in their team, they develop a sense of ownership over the content

students learn more about their case study than if they simply read it because they have to explain it to others

every student gets a chance to practice explaining science to their peers in a low-stakes environment

students get both depth and breadth of topics

most students love it, too3

This exercise is great when you don’t need students to become experts in a specific topic, but rather can benefit from different students developing expertise in different topics.

I am certain my students will forget biology-related terms, concepts, and details after my course is over. But I’m confident they’ll remember that every day in their science course, they made conclusions based on data.

If the only thing they remember about their study of science is that scientific “facts” are based on evidence, then that’s a win in my book.

Sometimes the figures are from one paper, often they are from 3-4 related papers.

I use Data Nuggets throughout the semester to give students practice graphing data. (But don’t they get that practice in your lab section? you might ask. That’s a can of worms, but suffice it to say, at my institution, the lab curriculum for Gen Bio II doesn’t involve any data collection or analysis.)

On last year’s course evaluation, one student said, “Can you make the entire course based on Jigsaws?”