Effective & Equitable Teaching Isn't Free

It costs time

Last week, I took my first exam in 20 years. It was in my introductory physics course, a class I’m taking at my community college because I’ve never taken physics before, and because by being a science student again, I hope to become a better science educator.

We got our exams back on Tuesday. While the instructor was handing back exams, she made an off-hand comment that illuminated a deeply powerful truth about systemic inequity in higher education.

Buckle up folks, it’s about to get real.

Here’s what my instructor said (paraphrased):

The average score on the exam was 71. If the average had been lower, I would normally offer a “points-back” assignment, but because this class is so large, I don’t have the time to grade it all. Instead, I would have curved the exam grade, but again, the average score was 71, which I’m happy with, so I don’t need to curve it.1

Let’s unpack this.

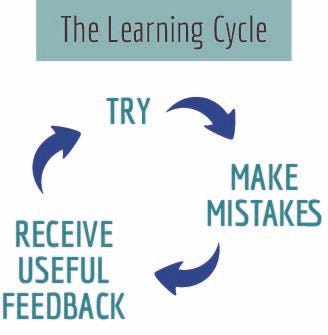

Effective & equitable teaching engages students in The Learning Cycle

My instructor said she would normally offer a “points-back assignment” after the exam. This is good teaching! Here’s why:

Learning is a mistake-making process and good teaching engages students in that process. Here is a poignant illustration of What Learning Looks Like:

In the video, a skateboarder tries a new move, doesn’t make it, receives feedback (in his body), and he tries again, and again, and again. Eventually he makes the move, and he is able to repeat it consistently afterward.

Although our students usually learn classroom content in less physical ways, learning still occurs like this: a novice tries something new, makes mistakes, receives useful feedback, and tries again. I call this The Learning Cycle.

Engaging students in The Learning Cycle is both effective and equitable. We have lots of evidence to support this claim:

Active Learning. Active learning activities are interruptions to lecture that engage students in recall, problem-solving, discussion, and other activities that require students to practice using new concepts or skills during class time when they can receive immediate feedback from the instructor. Incorporating active learning activities in the classroom, instead of straight lecturing, increases student learning and reduces the performance gap between historically disadvantaged and advantaged groups.

High-Structure Courses. High structure courses incorporate regularly-spaced learning opportunities throughout the semester, such as weekly homework assignments and frequent low-stakes quizzes. This course format forces students to practice spaced retrieval — i.e. engaging in the material regularly, rather than cramming before an exam — which results in deeper, longer-term learning. High-structure courses increase student learning and reduce the performance gap between historically disadvantaged and advantaged groups.

Growth Mindset. Growth mindset is the belief that a person’s skills and aptitude can change with deliberate practice, rather than being inherently built-in. Engaging in The Learning Cycle requires a growth mindset, because mistakes are viewed as positive effectors of learning, rather than evidence of failure. Interventions that increase student’s growth mindset reduce the performance gap between historically disadvantaged and advantaged groups, and instructors who have growth mindset have smaller performance gaps between historically disadvantaged and advantaged groups in their classrooms.

My physics instructor’s instinct to offer a “points-back” assignment is a great way to engage students in The Learning Cycle: students try by taking the exam, we receive useful feedback on the exam, and we get to try again by completing the points-back assignment.

But she didn’t offer it! Because it would take too much time.

Effective & equitable teaching costs time, and time costs money

The interventions I listed above all take instructor time. While growth mindset interventions don’t necessarily take much time, implementing active learning and designing high-structure courses can be very time-intensive. To implement active learning, I need to write or design my own classroom activities, or take the time to find, sort, and adapt activities from online. To implement a high-structure course, I need to assign regular homework assignments - which means writing them myself or finding, sorting, and adapting resources from online - and I need to write and grade frequent low-stakes quizzes. Additionally, if I’ve structured my grading system to support The Learning Cycle, I need to provide quality feedback on student work so they can make revisions or retry attempts, which I also need to grade. Whew, I’m exhausted just writing it all.

My physics instructor has a learner-centered instinct – to offer a “points-back” assignment that would engage students in The Learning Cycle – but she doesn’t have the time to grade it, so she doesn’t offer it.

She doesn’t have the time because she teaches as an adjunct. An adjunct position is a part-time, contractual position; she is only teaching one course at my community college this semester. I also teach as an adjunct there, so I know about how much she makes: roughly $4000 for a full semester (7 hours per week in the classroom & lab). I don’t know if she’s teaching elsewhere, but I do know people who assemble several adjunct positions per semester at multiple institutions just to make a living. If she assembled 4 adjunct positions per semester, including summer term, she would make $48,000 per year without benefits. If she did that, she would be expected to spend 28 hours per week in the classroom/lab with students, which doesn’t include the time to commute to each institution, time for course prep, grading, setting up the course on the Learning Management System, or other administrative tasks. No wonder she doesn’t have the time to offer extra graded assignments in our course!

Let’s be clear where the blame lies here: it’s not on her, it’s on an academic system that undervalues and underpays VITAL instructors (Visiting, Instructors, Temporary, Adjunct, and Lecturers). Of course, it’s not enough to pay our instructors more or reduce full-time instructors’ teaching loads. Faculty need to know what practices are most impactful for improving student learning and equity in the classroom, and they need the tools to implement them well.

But when the labor to create high-structure, active-learning-centered classrooms is uncompensated and unrewarded, change will be minimal at best. And when it comes, it will be carried on the backs of educators who have the passion and the privilege to invest extra time and energy, often at the cost of their own work-life balance.

I want to hope that the system can be different. I want to hope that institutions can advance effective and equitable teaching, not only by offering professional development opportunities, but by actually compensating instructors for the time and effort it takes to make their classrooms into more effective and equitable learning environments. In most US higher education systems, this is not the norm.

A brief plug: My textbook will reduce the time-load for effective and equitable teaching

I’m writing a new General Biology textbook, and one of the things I want the textbook to do is reduce the time-load for instructors to engage in the high-impact teaching strategies we know improve learning and classroom equity. Here’s how:

Active Learning Activities. Our (digital-first) textbook will include an “Instructor Edition” that includes a curated list of active learning activities that align with the learning objectives of each chapter. We plan to make it as easy as possible for instructors to find, choose, and implement active learning activities from our resource library, so they don’t have to spend time writing them or searching online for relevant activities.

High-structure course. The textbook will incorporate formative assessment questions with immediate feedback to help students engage in meaningful practice while they read2. Additionally, our online homework platform will include thousands of high-quality homework questions that are easily assignable by instructors to engage students in meaningful practice after class. Finally, we plan to provide a robust test bank that includes questions instructors can use on frequent low stakes assessments.

I don’t like the way it sounds like I’m trying to sell you something, because it feels like I have an ulterior (financial) motive. The truth is, I know how much time it takes to design a high-structure course with lots of active learning, and I want to make it as easy as possible for other instructors to do the same. Writing a textbook with these types of resources is one way I can help do that.

Our textbook isn’t published yet, and it won’t be for another few years. But if you want to receive email updates, review opportunities, or get exclusive previews of the material, you can sign up here.

Not everything you read on the internet was written by a human. For full transparency, here is how I used AI to help me write this post:

I asked Claude to help me brainstorm ways to write the sentence “But when the labor to create high-structure, active-learning-centered classrooms…” Claude’s suggestions stimulated my thinking about what I wanted to say in that sentence, but all of the writing in this post, including that sentence, was written by me.

In today’s post, I focus on her statement about not having enough time to grade the “points-back assignment” but her off-hand comment about grading on a curve is another can of worms. Grading on a curve is deeply problematic. But that’s for another blog post.

Many students today don’t like to read, especially not from a digital textbook. But don’t worry, we’ll meet them where they’re at: Each chapter will include professionally-narrated video segments of 5-10 minutes using the text of the chapter as the script. Visuals will include static slides that highlight key terms and concepts, as well as static and dynamic multimedia from the chapter.

I went to a talk by Keith Sawyer a few weeks ago (he is at UNC, so in your neck of the woods)(https://ed.unc.edu/people/r-keith-sawyer/) where he also talked about how good, effective teaching is expensive. It takes a lot of time and effort!

Really great unpacking of that instructor's comment, both explaining why it is problematic and explaining why she can't be blamed for not creating even more work for herself. Ben Wiggins and I tried to do a very similar dance (pointing out missed opportunities for equity while also sympathizing with instructors' practical constraints) in our December 2024 HAPS Educator article on undergraduate A&P instructor exam practices.