Grading Policies that Hurt or Helped my Students

Note: This was originally written on May 11, 2023 and posted on my personal website.

For the last few years in my General Biology community college courses I’ve been experimenting with various large- and small-scale grading policies. As the school year wraps up, I’m reflecting on the grading policies that hurt or helped my students, and what I plan to do in future semesters.

Grading policies that hurt my students

Late Work Tokens

I love Late Work Tokens. They help strike a balance between high course structure (students need deadlines!) and flexibility (sh*t happens!). At the beginning of the semester, I give students a set number of Late Work Tokens that they can use to turn in specific types of assignments late. Basically, Late Work Tokens provide deadline flexibility for students who need it, while still promoting deadline structure for students who need it. (I’ve written more about Late Work Tokens here and here is a 25-min recording of a talk I gave on Equitable Late Work Policies at The Grading Conference in 2022.)

But this semester, my Late Work Token policy hurt some of my students. The problem came from these elements of my course structure:

1) Students could use a Late Work Token to turn in an assignment any time until the end of the semester

2) The primary assessment in the course was 3 take-home Essay Exams

3) Students could submit Exams late using a Late Work Token

While some students used a Late Work Token to turn in an Exam a few days or even a week late, a couple students put off one or more exams until the end of the semester. (The exams were not cumulative.) One student didn’t turn in any exams and tried to complete them all during the last couple days of the semester. My exams are long and hard, and that student didn’t budget enough time to complete all three; they failed the class in large part because they ran out of time and had to submit one of the exams mostly incomplete.

Additionally, students could complete a structured revision of every exam, but students who waited until the end of the semester missed out on the revision process. There just wasn’t enough time for me to grade the exam and have them use my feedback to submit a revision during the last couple days of the semester.

I thought the natural consequences of waiting to submit an Exam until the end of the semester would deter students from doing it unless it was absolutely necessary, but I underestimated how much deadline structure they needed.

What I’ll do differently next time. Rather than giving students 3 Late Work Tokens they can use to turn in an assignment any time until the end of the semester, I will give them ten “24-Hour Deadline Extension Tokens.” Like always, students with extraordinary deadline challenges can still earn more Tokens by meeting with me one-on-one to discuss time management strategies and set personal deadlines. This still provides flexibility – including for exams! – but it eliminates the possibility of waiting until the end of the semester to complete a high-stakes assignment.

Giving points in addition to detailed feedback on Exams

I gave substantial, personalized written feedback for every exam, and students had the opportunity to use that feedback to submit a structured exam revision. However, I also use a points-based grading scheme and publish the points earned on each exam alongside the feedback. I know research has shown that students are less likely to read and benefit from written feedback if it is given alongside a numerical score (see Butler & Nisan 1986 and Lipnevich & Smith 2008), but I’m not willing to give up a points-based scoring system because I think it still has advantages (as long as you don’t make common points-based grading system errors). So, despite the evidence, I’ve been releasing substantive feedback AND points together.

But I know that at least some students didn’t read the feedback because, in one case, during an in-person conversation with a student I referenced a comment I had made in their exam feedback, but they hadn’t read it at all. So, can I keep a points-based grading system while also encouraging students to read the feedback?

What I’ll do differently next time. Here’s my brilliant plan to bridge the distance between the feedback-centered benefits of #ungrading and the benefits of using a points-based system: delay giving the points until after a “feedback-only” moratorium!

I grade each exam question using the EMRN rubric and in their feedback, for each question I write the letter they earned and if it’s not an E, what they can do to improve their answer. The purpose of the feedback is to provide guidance to help them improve their understanding and performance on the revision.

Although I think it might rankle some of my colleagues in the Alternative Grading community, I overlay points to the EMRN rubric using this formula:

E = 2.5 points

M = 2 points

R = 1 point

N = 0 points

For an exam that has 4 long-form questions, getting 4 E’s would mean getting 10/10 = A, 4 M’s would mean getting 8/10 = B, whereas 4 R’s would mean getting 4/10 = F. That feels appropriate, because the difference between M (meets standard) and R (revision needed) is that “significant gaps remain”.

So, students get feedback that looks like this:

1- M (you don't explain "how ethanol production contributes to regenerating one of the inputs of glycolysis during yeast fermentation." - you talk about regenerating ATP, but that ATP is used by the cell! what other input needs to be regenerated through the process of fermentation?)

2 – R (review what happens to the CO2 that gets incorporated in the Calvin cycle – what molecules does it get turned into? Clarify what you mean by “When there is no light, the calvin cycle can be done since it doesn’t require light but the results can’t be used to make the necessary molecules”)

3 - E

4 - E

Notice that the feedback doesn’t have any points! But I always calculated each student’s Exam score (for the student above, 2 + 1 + 2.5 + 2.5 = 8/10) and I would enter the numerical score in the “grade” field in our LMS.

So my brilliant idea (I’m convinced this is brilliant) is to give the same written feedback plus EMRN score, but wait one week after releasing the feedback before posting each student’s numerical grade! That way, once the exam is graded, students can review the feedback – and, if they want to, they can calculate their grade themselves! But they have to review the feedback to get their grade. I’m hoping this works as well in reality as it does in my head. Stay tuned.

Grading Policies that Helped my Students

Learning Community Contributions

A small portion of the final course grade (3-5%) came from student’s “contributing to our learning community.” The point here is to incentivize students collaborating and helping each other.

Here’s how it worked: At the beginning of the semester, the students generated a list of actions that would count as “contributing to our learning community.” (Here’s the list from my spring semester General Biology course.) In the middle of the semester, I had a short in-class activity where students self-assessed what they had already done and what they still planned to do to contribute to our learning community. At the end of the semester, students completed a reflection in which they described how they contributed to our learning community (including providing evidence for at least one of three different ways they contributed).

As I’ve written before, this was one of the most impactful grading policies I’ve ever implemented! Both last Fall and this Spring, students set up their own Discord servers for the class and I heard repeatedly about how active the Discord server was. I’ve never had classes that felt as cohesive and community-centered as my classes this year. This was, by far, the most impactful 3% of the grade I’ve ever allocated.

Multiple Grading Schemes

I use a points-based grading system and I provide multiple grading schemes that weight different components of the course differently. I’ve written about it and made a 6-minute Youtube video about it, so I won’t go into too many details here.

But I do want to point out two important benefits of this grading system:

1) Multiple Grading Schemes really does provide multiple paths to success for students with different strengths. Students who understood the material well but didn’t do the (pre-class) homework were not penalized. And students whose assessement scores were borderline or close to the next highest grade could get a grade boost if they had completed all of the homework.

2) Preliminary data from my courses and dozens of math courses at my community college show that Black students especially benefit from Multiple Grading Schemes. This is on-going research, so stay tuned to learn more (I’ll be talking about it in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning session at the online Grading Conference this June 9-10).

Grading Homework on Completion Only

I’m a big proponent of grading Activities that Promote Learning on completion only. I assign pre-class homework that is designed to prepare students for class. I don’t used a formal “flipped classroom” format, in the sense that I don’t record me lecturing [boring!], but I do assign YouTube videos and various reading assignments from the internet accompanied by a series of questions students should answer and post to our LMS.

There are two incentives for students to do the homework:

First, they get graded 0 (incomplete) or 1 (complete) for the homework. I do not check for correctness, because the homework is designed to introduce them to concepts – I don’t expect them to have mastered the content yet! I have never found an instance where students cheat by pasting the same answers as another student or pasting nonsense text. I usually don’t check every student’s answers, I just assign 0 or 1 for completion and do a quick pass through some students answers to get a gestalt feeling for what they easily understood from the homework and what’s challenging. This saves considerable time for me while still maintaining the high structure of expecting them to do – and submit! – homework before every class period.

Second, in class I assume they have certain background information that they should have gotten from the homework. I literally say, “Ok, since you did the homework you know XYZ so now I’m going to ask you to think about ….” Students who didn’t do the homework are at a disadvantage, but I still design the in-class activities in such a way that students who didn’t do the homework can still participate. (It’s worth mentioning that almost every in-class activity involves students talking with team members, so students who didn’t do the homework can learn from those who did.) This way, I create an incentive to do the homework without crippling students who don’t do it.

Ungraded Exit Questions

I save 3-4 minutes at the end of each class period, for students to write a response to an “Exit Question,” which they submit on note cards (or torn off pieces of notebook paper). I try to design the Exit Questions to be practice for some of my longer form Exam questions. These are not graded at all. I use the responses to craft the beginning of the next class period, so I can directly address common misconceptions that are specific to my students, right now. My students reported that one of the ways they prepared for the exams was by taking the Exit Questions seriously and doing their best to answer them, since they knew it was practice for the Exams. I really like Exit Questions because they are no stakes, time-on-task learning opportunities for my students to practice evaluating and synthesizing information in a format that prepares them for the Exams, AND I get formative feedback from the students about what instruction they still need!

Exam Revisions

As I mention above, my Exams are hard: they involve high Bloom’s-level questions (evaluation, analysis, synthesis) and I expect paragraph-level answers. Additionally, most of my questions ask students to support their claim using evidence from our course Figure Gallery, which is a collection of all the data figures we’ve discussed in the course. The questions are hard, but the Exams are take-home, open-book, and untimed. (Yes, I need to figure out how to AI-proof my Exam process, because I do need to know what my students can do, not just what ChatGPT can do.)

After students have received my feedback on their exams, they can submit revisions. I’m a big believer in the iterative nature of learning and I think it’s artificial to ask students to master a concept or skill on the first try. Of course, the semester format is artificial and provides it’s own constraints, but within those constraints I try to create an environment where students can learn from their mistakes. There are different ways to structure exam retakes or revisions, and my way isn’t the only way, but it’s one way to focus on learning over time rather than one-shot-only performance-oriented assessment.

(NB: I still haven’t figured out how to get more students to submit revisions, an equity-issue that I wrote about at the end of this blog post and which still nags me. But offering exam revisions is better than not offering them at all, so at least there’s that.)

Final Thoughts

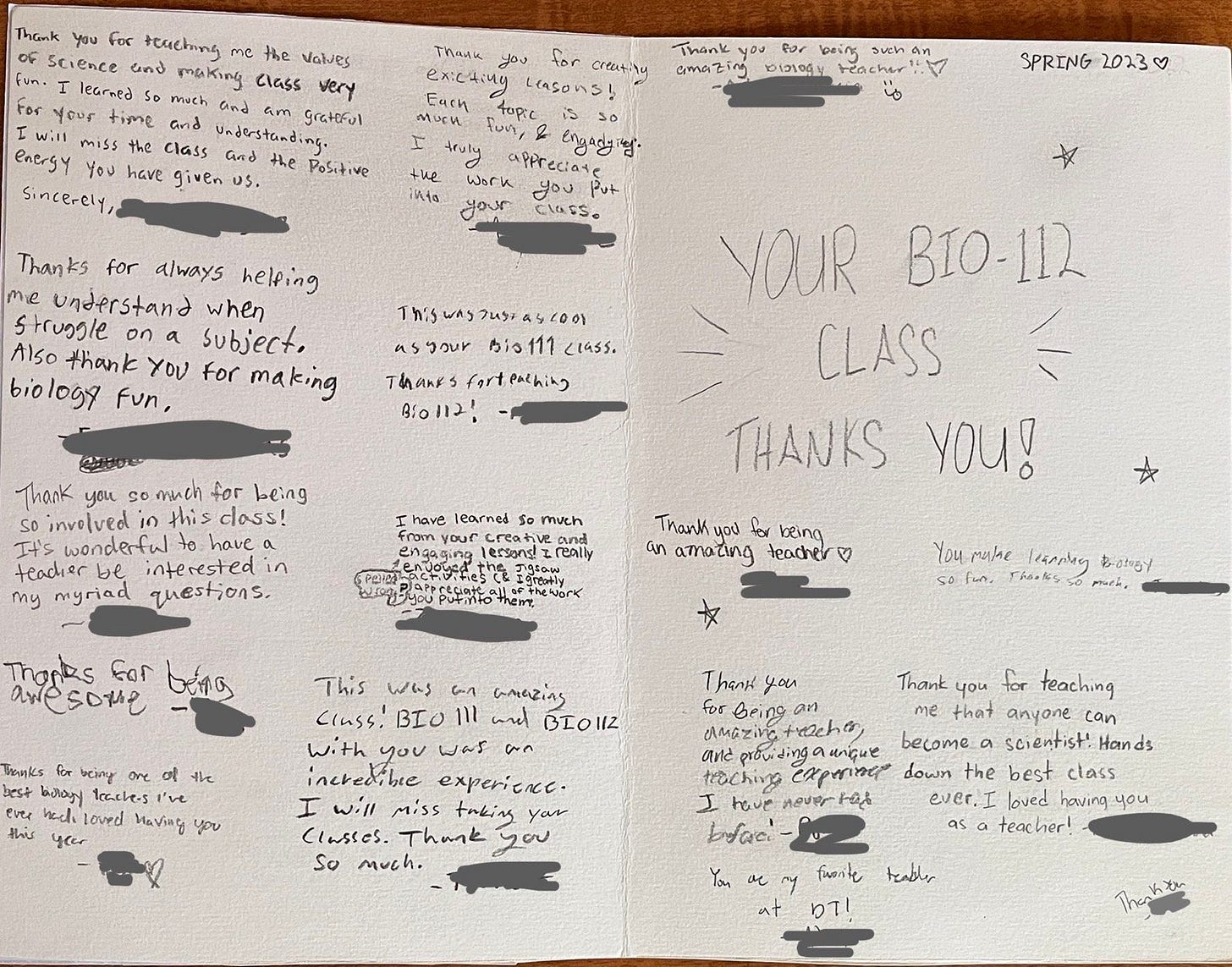

If you read my last blog post, you know that, in addition to the grading policies that hurt my students from above, I made some significant other mistakes in the grading structures for my spring General Biology course. It wasn’t all bad, though. In addition to this class being more tight-knit and community-oriented than any other class I’ve taught, they also expressed significant appreciation for me. At the end of the semester, I received multiple hand-written notes, including one from the whole class. I’ve never received such an out-pouring of appreciation from a class before!

While I think it’s important to focus on areas for improvement – how else can we grow, learn, change, and become better educators?! – I also think it’s important to celebrate our successes! I’ll end with this touching note from one of my students: